Portrait of a Woman in a Black Dress Carnegie Museum

Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, an American-born expatriate who had been living in Paris since 1867 after she moved there with her widowed mother when she was 8 years old, was a celebrated socialite there.

A pale-skinned brunette with fine, cameo-like features and an hourglass figure, she was known to use lavender-colored face and body powder to enhance her porcelain complexion, dye her hair with henna, and color her eyebrows. She became one of Paris' conspicuous beauties and was in fact known as a "professional beauty" — a woman who audaciously used her appearance to gain celebrity and advance her social status, which is something she did exceptionally well.

Virginie Amélie Avegno, circa 1878.

Public domain photo via Wikimedia Commons

She attracted much admiration due to her elegance and style. She also attracted notoriety: In 1887, she married wealthy French banker and shipping magnate Pierre Gautreau, who was much older than she was, and soon Paris was buzzing with rumors about her alleged multiple infidelities.

The social elite still clamored to be around her, though, and artists were particularly fascinated by her unconventional beauty. Edward Simmons, an American art student living in Paris, proclaimed her to be a goddess and confessed that he "could not stop stalking her as one does a deer," according to Deborah Davis in her book, Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X.

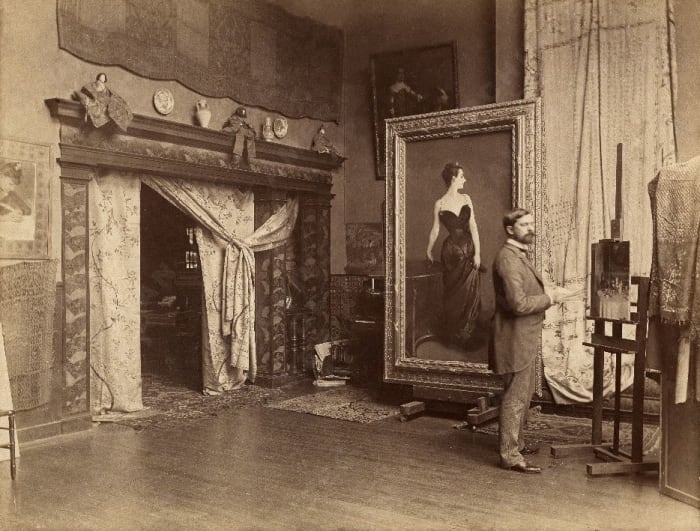

Gautreau also caught the eye of ambitious young American artist John Singer Sargent. Sargent, who made his name with his work in portraiture and was a rising star in the Paris art world, was desperate to paint her, believing a portrait of her would make his name. In 1883, he finally convinced Gautreau to pose for him, with the intention of creating a masterpiece to exhibit at the Paris Salon in 1884. Sargent hoped it would lead to critical recognition and portrait commissions, but it nearly sidelined his career instead.

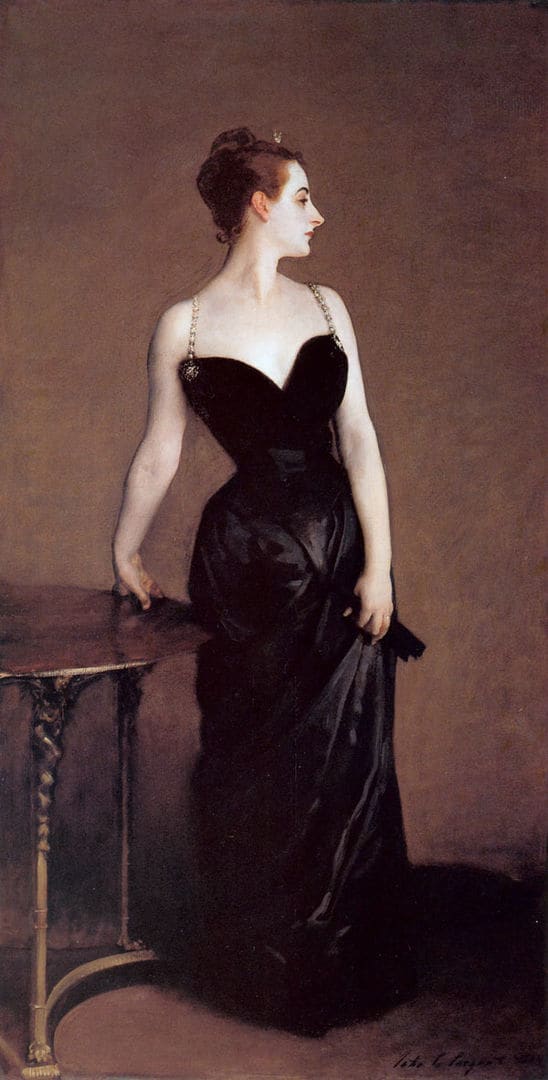

Since Gautreau was a fashionable woman, it's no surprise that she chose to wear something fashionable for the portrait: an elegant black evening dress with a heart-shaped velvet bodice and jeweled straps, which is the sort of dress that would have been worn in Paris, and black was a popular color for evening wear. She accessorized it with her gold wedding band, a diamond crescent hair comb, and her powdered skin, and she is carrying a black fan. In Sargent's original painting, one strap has slid down her shoulder.

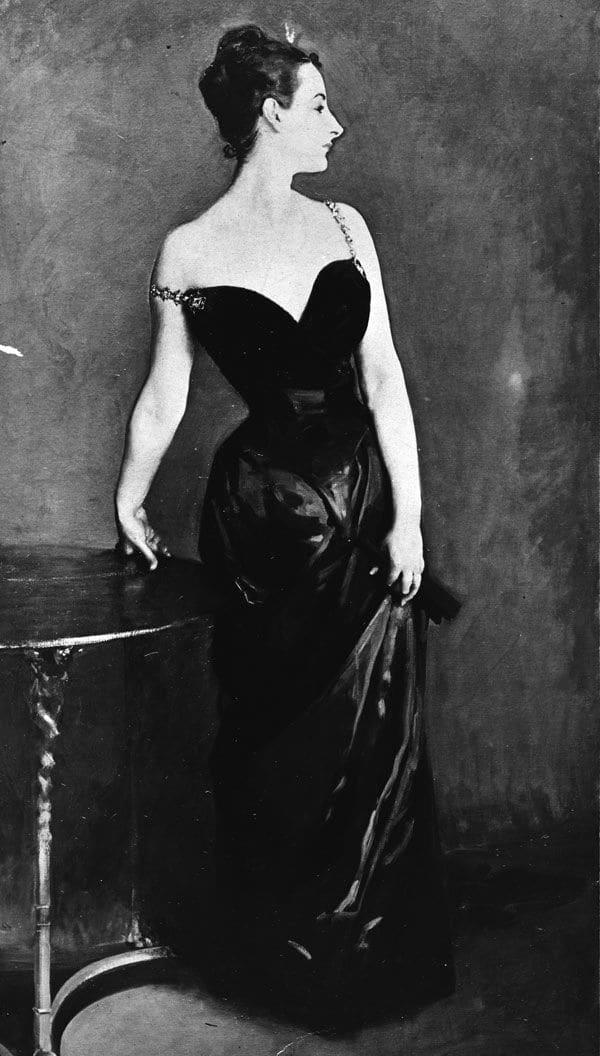

The original version of Madame X, with the scandalous dress strap falling off one shoulder.

Courtesy of the Met Museum

When the portrait was unveiled at the Salon in 1884 under the title, Portrait of Mme***, the two Americans did what seemed impossible in a city that had seen it all: they shocked the French. Parisians were not only shocked, they were scandalized and horrified. Perhaps magnified by the fact that the painting did not cause a row at just any exhibition, but at the Salon, the prestigious, officially selected exhibition that had been the center of artistic life in Paris since the 17th century, the art critics absolutely hated it. They hated Gautreau's oddly pale skin, they hated the pose, and they especially hated the cleavage-plunging dress that, according to one critic, looked as if "One more struggle and the lady will be free." Another French critic wrote that if one stood before the portrait during its exhibition in the Salon, one "would hear every curse word in the French language."

In a review of the 1884 Salon, The Times reported: "Sargent is below his usual standard this year … The post of the figure is absurd, and the bluish coloring atrocious. The features are so exaggerated that the natural delicacy of outline is entirely lost. Under Sargent's brush, the 'so-called beautiful' subject looked like a mere 'caricature.'"

This was because Gautreau's suggestively coquettish pose and revealing costume so offended French sensibility as indiscreetly suggesting the woman's reputation. It wasn't that a woman of Gautreau's station in society would not pose as a model (after all, no scandal was attached to her later posing for two other artists), it was that Sargent was seen as having openly defied convention by flaunting the woman's immoral lifestyle.

Critics also didn't object to the display of décolletage, but the lack of fleshiness or sensuality, with Henri Houssaye, art critic for the Revue des Deux Mondes, writing: "The décolletage of the bodice doesn't make contact with the bust, it seems to flee any contact with the flesh."

Gautreau's dress, possibly one designed especially for her, is a dramatic simplification of a style for pointed-front bodices and narrow straps that had been recently fashionable, but without the tiers of lace or decorative swags of flowers one more typically finds at that time. Thus, it was not necessarily the dress itself that prompted scorning, but instead Gautreau's way of wearing it (with the slipped shoulder strap and heavy make-up). Also shocking was her almost certain lack of undergarments:

"Heavily boned, the cuirass had a plunging neckline and came to a deep, sharp point over the crotch. 'Though the cuirass would have had some kind of lining to soak up sweat, the model would not have been wearing any underwear,' said Valerie Steele, director of the museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, and that would have been scandalous," according to a New York Times article.

After the Salon, Madame Gautreau was ridiculed and mocked by Paris society; viewers of the painting understood her bare shoulder, with its dangling strap, and her exposed cleavage, as a nod toward her rumored loose sexual morals. Her furious mother ordered Sargent to remove the portrait from the Salon, and reportedly lamented, "All Paris is making fun of my daughter ... She is ruined. My people will be forced to defend themselves. She'll die of chagrin."

Since the piece was not commissioned and he therefore owned it, Sargent refused. He did, however, later repaint the final portrait with both straps on Gautreau's shoulders.

John Singer Sargent's "Madame X," with both shoulder straps in proper place; 82-1/8" x 43-1/4". This is now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Courtesy of the Met Museum

Gautreau never fully recovered from the scandal and retreated from Parisian society for a long time. She did later have two other portraits done, including one by French artist Antonio de La Gándara. He painted a full-length portrait of her in 1898 titled,Portrait of Mme Pierre Gaudreau. The colors and style of her dress are more conservative than Sargent's painting and this was reportedly her favorite.

"Portrait of Mme Pierre Gaudreau" by French artist Antonio de La Gandara, 1898. This was reportedly her favorite portrait. It's now in the collection of the Gibbes Museum of Art.

Public domain photo via Wikimedia Commons

French artist Gustave Courtois' painting, "Madame Gautreau," 1891. The slipped strap in this painting didn't cause outrage.

Courtesy of Musée d'Orsay

Sargent, meanwhile, was concerned with his own reputation and after getting lambasted by critics, he escaped his infamy in Paris and fled to London, where he lived the rest of his life. He went on to be a huge success and became of the most famous portrait artists of his age.

He kept the portrait in his studio for many years, and eventually sold it to the Metropolitan Museum in 1916, on the condition that it be titled Madame X. According to the Met, when Sargent sold them the piece, he wrote to the director, "I suppose it is the best thing I have ever done."

John Singer Sargent in his Paris studio, circa 1883-1884.

Public domain photo via Wikimedia Commons

It now hangs in the American Wing of the museum and is considered a masterpiece, much admired for the elegance and virtuosity of its execution. It is also unlikely that anyone who looks at it today will get the vapors.

The infamy of the dress itself has lived on. In 1960, Cuban-American fashion designer Luis Estévez created an iconic black dress based on Gautreau's. Actress Dina Merrill, daughter of Marjorie Merriweather Post, modeled the Estévez dress in Life magazine in January 1960 and recreated the painting, as well as the work of other artists in a series of photographs by Milton H. Greene. According to Couture Allure, the dress sold for $125 in 1960. It went up for auction in 2012 and was valued between $6,000-$8,000, but it didn't sell.

Luis Estevez's 1960 interpretation of the Madame X dress.

Courtesy Kaminski Auctions

Gautreau's chic garment at the center of Sargent's artwork may be Madame X's greatest legacy. It is still influencing fashion today and models and actresses channel her style on red carpets and runways — proving that a good black dress is timeless.

You might also enjoy:

Inside the Closet of Marjorie Merriweather Post

Pioneering Fashion Designer Ann Lowe

Vintage Dresses Celebrate Spring

Lady Mary Curzon's Phenomenal Peacock Dress

Source: https://www.antiquetrader.com/collectibles/how-the-black-dress-in-madame-x-scandalized-paris-in-1884

0 Response to "Portrait of a Woman in a Black Dress Carnegie Museum"

Enregistrer un commentaire